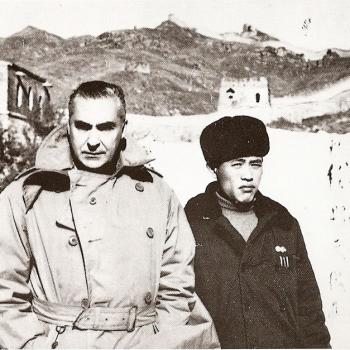

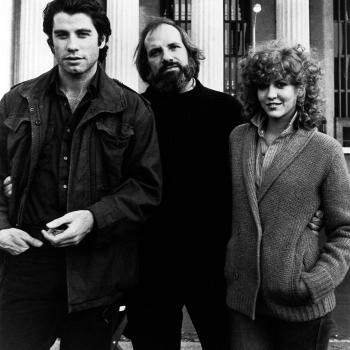

Source: Flickr user Breve Storia del Cinema

Public Domain

I don’t like saying movies age poorly. It feels impolite like asking a lady her age or inquiring about that Argentinian friend with a German last name’s grandpa. You just don’t do it.

But even I have to be honest with myself sometimes. It ain’t easy. I’ve spent a lifetime convincing loved ones that just because a movie is black and white or silent or slow that it’s still worth seeing. Throw in that I’m a “medievalist” and it’s built into my whole shtick: uphold the old. Just because it’s a little dusty doesn’t mean it isn’t better than your shiny new whatever.

Let me get this off my chest: Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1960) has aged poorly. But, before I get there, let me sing its praises.

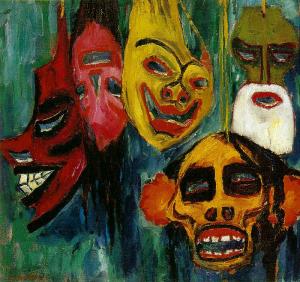

As we know from Dead Ringers (1988), nothing is scarier than a surgeon who has lost his (yes, his) mind. In Cronenberg’s film, the twin chop doctors work in reproduction. At first, they exert their power by drawing life where it otherwise refuses to be. By the end, the two twist themselves and their patients’ bodies, reforming what it means to be a human being (and especially a woman). In Eyes Without a Face, our lead is Dr. Génessier (Pierre Brasseur), a square-headed, bearded lug of a man who promises great leaps in the science of heterograft surgeries. He is a cosmetic surgeon bent on remaking science and human possibilities not (merely) on account of self-aggrandizement but because his own daughter, Christiane (Édith Scob), has been horrifically disfigured (in a car accident he caused, but never mind that…). As a result, she wanders his suburban mansion in the mask that inspired Mike Meyers’ own famous blankness. He spends his days researching while his assistant lures women to the house so that he can try to remove their faces to graft onto his own daughter. He keeps failing. Oh well. Time for more experiments.

Isn’t that spooky? It’s got it all: the troubled, sympathetic mad scientist whose pursuit of progress manifests barbarism (an impulse and result that seem to undergird most “innovation” today—a prescient idea from Franju’s source material). The lonely, masked woman skulking candle-lit halls, yearning for freedom and not trusting her own father, her maimer. We’ve got murder, intrigue, and a terminal sadness that hovers over the whole film.

The score is phenomenal. We open in a car, the camera looking out at blank trees jutting into a bleak, nighttime horizon as the vehicle drives on. What sounds like circus music blares over the receding night, a darkness that keeps disappearing and coming again, an inescapable fact. Wherever we are it is both far out “there” and not far enough from whatever evil lurks in these half-forested hills.

While the film’s producers saw it as an early Italo-French horror venture, Franju disagreed. For him, Eyes Without a Face was a nightmare, yes. But a nightmare is a kind of dream. His vision was for a fantastique style haunting, small doses of horror drawn out across stretches of anxious restlessness. Unsurprisingly, Franju’s description is closer to the truth. So much of the movie is characters walking or driving, skulking the halls of the doctor’s mansion, making their way down long roads between Paris and this suburb, that it takes on a hypnotic quality. In some cases, this dreamlike plodding builds tension in the viewer (e.g., when we first meet Christiane and are unsure if we will see her scarred face, her mask, or both). Often these long sequences are gorgeously shot and lit, unnerving in their tranquil, silent beauty.

But that’s also the problem: the film is largely composed of these sequences, and, when they aren’t building to anything, they induce something else associated with dreams: sleep. Franju so successfully accomplished his vision that the movie’s quiet anxiety sometimes passes into a hypnotizing lullaby. The Doctor creeps. Christiane skulks. Louise (Alida Valli) drives. All in silence. There’s horror based on mood, and then there’s Eyes Without a Face.

Maybe I have been spoiled by the manic pace of so many modern scary movies (heck, movies in general). But I don’t think so. I’ve got a taste for the slow and the deliberate. What I need, though, is for that capaciousness, that willingness to sit with the material, to build from or toward something. Eyes Without a Face seems to relish these long pauses more than the horrors themselves; it draws you in, lets you know what’s going on, and then keeps tracking its characters slowly even though we already know the score.

Audiences at the time were reportedly scared by the film. And why not? Some of its images are seared into my brain (not least Christiane’s blank expression, the impenetrability of that mask). Its first song makes my skin crawl. But the quietness of silent films, the excitement produced by watching a person walk the same steps lit by moon- and candlelight, has faded with time. Progress? I’m unsure. But, in this case, Dr. Génessier’s vision might just have won out.