Source: Flickr user Susanlenox

Public Domain

I did not shoot the sheriff. I didn’t even shoot the deputy. And I most certainly didn’t shoot Bambi’s mom. Word on the street, in fact, is that she was never shot at all, that the chief execs over at Disney imagine a happier, less-traumatized Bambi, one whose turnaround will both reflect and produce happier, less-traumatized kid audiences. Or maybe the whole thing is a PR campaign. All press, good press—that canard. Certainly, the right-wing media sphere has its meat for the week. Surely, some noble liberal parents (or heck, childless adults) will soldier on over to Disney+ and protect the young hart.

The news got me wondering about childlike melancholy. Some childhoods are easier than others. Indeed, some can barely be said to exist. But popular portrayals of the young only dip their toes into sadness, flirt with the idea that things won’t work out, though of course they do. Our collective imagination of kid-hood is one of magic, of wonder, of unflinching optimism. The dirty little secret, however, is that kids get sad too. They understand more than they let on, sometimes (as South Park loves to show us) more than adults. Balanced in this liminal space between hope and sorrow is what I’m calling “childlike melancholy.” It’s that lead-heavy diamond in your stomach when, on a bright summer day, your friend falls and snaps his leg in half. It’s the welling tears when you overhear the word “cancer” or “divorce” spoken in hushed tones from across the kitchen. It’s that time in 2007 when the girl of your underdeveloped dreams agreed to date you after a long night together at the Jersey Shore only for you to get into the car filled with excitement and dread. Two days later you’re sick, watching early episodes of iCarly when she breaks up with you via text. You knew that dread came from somewhere—every dream a nightmare…

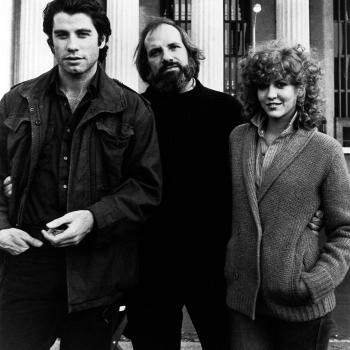

Takeshi Kitano’s (I’m reverting to the more typical English mode—so sue me) Kikujiro (1999) captures just that halcyon moment plagued by its own negation (or worse). The formula is nothing new: Masao (Yusuke Sekiguchi) is a young boy who lives in a working-class part of Tokyo with his grandmother. Dad’s long gone and Mom is far off, working to help support him. Grandma is always working and his friends have lives (and families) of their own as the school year ends. Bored with nothing to do on summer break, he sets off to find his mom (who lives at the beach—always a symbol of bliss in Beat Takeshi’s films) accompanied only by his grandmother’s friend’s husband, Kikujiro (Takeshi Kitano). The middle-aged man is a low-level gangster (think lower than Bart Simpson when he starts working for Fat Tony) who is ruder than a summer day is long. He only wants to drink, gamble, and pick up prostitutes. So, of course, what little money Masao has he immediately spends at the bike track (that’s Japan for you), praising the kid when he picks a winner and then relentlessly screaming at him when he fails to pick right each time thereafter.

The formula (really the plot) in Kitano movies is a skeleton. It’s there; it’s sturdy; you need it. But it’s best when invisible and unremarkable. Nobody wants someone to look at their spine and ooze, “oh my!” The two slowly bond as the little boy tempers the half-wit gangster and vice versa. Masao comes out of his shell, helping his “mentor” with his schemes; Kikujiro becomes protective of his little companion, saving him from danger and manufacturing increasingly absurd ways of keeping him happy after things take a very sad turn.

What’s remarkable is what actually happens along the way. I don’t just mean the ole id est, some truism about facticity. No, Kikujiro is about an emotional tapestry that weaves joy and sadness so tightly they can’t be separated. It gets dark, including a brief (and unexpectedly graphic) kidnapping of Masao by, uh, let’s just say a Jimmy Saville type of Typ. What’s more bizarre: it’s played, in part, for laughs. Masao finds out what’s going on with his mother a little over halfway through. It ain’t great. The duo gets stranded at a rural bus station. They camp in a truck stop parking lot and try to muscle drivers into taking them further along. Masao is plagued by horrific dreams in which prostitutes that he’s seen around Kikujiro overwhelm him. In others, his kidnapper gropes and hisses at him.

Beat Takeshi got his start as a comedian though, and Masao’s journey starts to seem like the coolest summer vacation ever. Their scams for getting drivers to pick them up include faking blindness and hiding the old man and having the teary-eyed kid beg. They hang out at a ritzy hotel without paying a dime and meet fun-loving bikers and a hippy itinerant. The adults put on plays for Masao; they cheer him up by pretending to be aliens and playing the most fun version of Red Light, Green Light I’ve ever seen. All of them camp under the stars for days on end. The journey becomes (if you can forgive me another truism) the destination.

If kids’ movies are now made for adults, Kikujiro is an adult movie that captures the ambivalence of being a kid. It ends and begins with the same sequence: Masao running excitedly through the streets of Tokyo, his manic race with himself underlined by Joe Hisaishi’s ebullient theme. Childhood does often mean wonder and glee. But that joy is hard won, and even kids know that the world is a sad place. They just have the sense to love it, to hope for it, anyway.