Janine Giordano Drake

We’ve all heard the story: Abe Lincoln created the national holiday we call “Thanksgiving” in 1863. In the midst of incredible carnage due to war and disease, the “Great Emancipator”—at the urging of Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of the Godey Lady’s Book and Magazine—urged Americans to set aside a day of “thanksgiving and praise to Almighty God, the Beneficent Creator and Ruler of the Universe.” What we perhaps spend less time thinking about are the motivations for the holiday.

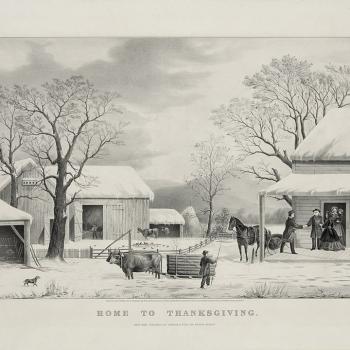

By the mid-nineteenth century, a version of Thanksgiving had already been in practice among middling-class Protestants in New England. It had been a church feast day which involved a special meal and maybe an outing for wild turkey shooting. Working-class men often treated the day as a “masculine escape from the family, a day of rule-breaking, and spontaneous mirth.” But, at Hale’s urging, Lincoln transformed the regional festival into a civic holiday which offered thanks to both God and the “kindness” of Indians for provision during desperate circumstances. In nominating the story of the Pilgrims and Indians as an origin story and mythology of American identity, Lincoln’s “Thanksgiving” created a white racial imaginary that would foster unity among whites. But this newfound “American” unity came at the expense of indigenous peoples and people of color.

If we think for a moment about the timing of this new national holiday, it was a strikingly manipulative effort. At the time, eleven US slave states were fighting an armed rebellion in defense of slavery. All Northern men were subject to mandatory conscription, but wealthy Americans were permitted to pay fines to escape military service. This meant that Union troops overwhelmingly consisted of poor men, including immigrants and African Americans, who served in the bloody and disease-ridden battle fields because they had no other choice. Lincoln also used the fact of wartime to pass laws which made it illegal to criticize himself and the war effort. He suspended the right of habeas corpus. To add to this moment a mandatory celebration of the US military, and Christian nationhood, was a brazen move.

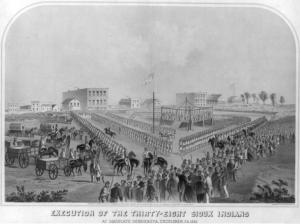

But to make matters worse, Lincoln also sacralized the origin myth of giving thanks to peaceful Indians at the precise moment that he was provoking war with indigenous nations throughout the West. Indeed, throughout the Civil War, Lincoln used Union troops to urge indigenous nations in the West to sign treaties which would dramatically reduce their homelands to much smaller reservations. When these nations refused to concede to the president’s orders, as the Sioux, Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Muscogee, and many other nations did, these nations came into armed rebellion against the Union army. Lincoln claimed that he authorized these wars in the act of securing “liberty” for “Americans” to homestead on their own property. But this concept of liberty was profoundly limited to white people, since Lincoln denied the entitlements of Native Americans to their own land. In the year 1864, many Western states did not even permit African American migrants to settle and buy land. This is to say nothing of the Mexican American land claims, dating to the 1848 Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo, which the US government and Southwestern states refused to honor.

What, then, is the American “liberty” that white Americans celebrated at the first national Thanksgiving? The mythology behind the holiday, of course, celebrates “good” Indians for their virtues of compliance and generosity in a time of great need. It implies that “bad Indians” are those who do not immediately hand over their property and comply to the demands of white settlers. When we look more closely at Lincoln’s words in his very first Thanksgiving Proclamation, we observe that Lincoln attributed land as a blessing at once from both Indians and from God. He conveniently avoided any distinction between these two sources of “national blessing.” As Lincoln put it, “He [God] has opened to us new sources of wealth and has crowned the labor of our workingmen in every department of industry with abundant rewards.” Lincoln’s use of the terms “us” and “our” is quite telling. At his very best, Lincoln was uniting white Americans of all classes, and across many regions, under the possibility of equality as settlers on stolen Indian territory. These narratives of “good” Indian giving were likely part of his project in selling the American public on the US military endeavor to dramatically reduce territory held by sovereign nations in the American West.

More than a century later, most of us think of our contemporary celebrations as far more innocuous. We are getting better at acknowledging Native American histories in the foreground of our stories of the “First Thanksgiving.” We are acknowledging that all US land has a history that predates European settlers. Many have changed the holiday to “turkey day,” a moment to reflect with family and friends on all those things for which we are thankful. But is it possible that even the act of gathering around a large meal, and thanking God for what we already have, is also a ritual of conquest?

When I think about the many material things which I am able to share with family on Thanksgiving, I find myself realizing that my access to many of these things was only made possible by violence, exploitation and theft—coupled with the nation’s effort to conceal this work behind the shroud of “thriving industry.” I think about European conquest of the silk roads every time I use my spice rack. When I measure out my sugar to put in my pumpkin pie, I think about the enslaved people whose “cheap labor” made the mass production of sugar into a universally recognized “good.” When I pull out my cotton tablecloth, and dress it with tea and coffee, I get lost again in the history of North American slavery.

To what extent is the abundance of food at my Thanksgiving table made possible only because of underpaid and overworked agricultural workers and meat processors? To what extent are our tastes the product of centuries of mass production which was only made possible because of the collusion between white supremacy and American capitalism? I do not know how much violence I condone or perpetuate on a daily basis because my country makes it easy for me to pay no attention to these production processes or the consequences of my consumption. In fact, in part because of our mythology of national Thanksgiving, Americans have long counted abundant consumer goods as the most visible emblem of American freedom.

As I reflect on what I have to be thankful for this Thanksgiving, I have given myself and my family a new puzzle to consider. Is celebrating what we have always an act of peacemaking? Is celebrating what we have, and what we expect to continue to have, sometimes an act of conquest over things that we have no right to claim? It is easy to see, more than a century later, that Lincoln’s celebration of the “new sources of wealth” in other people’s property was an act of war. It was probably harder for some white Euro-Americans to see that at the time; the act of settler colonialism was so deeply ingrained in nineteenth century American identity. What are our current blindspots? What are we thankful for this year which we have no right to claim as ours? Whose exploitation is at the foundation of our abundance? Whom must we scapegoat to unite as Americans? What theft do we participate in as we count it as our entitlement?

To ask these questions around the dinner table is to challenge the white supremacy at the foundation of this republic and return the holiday to a much more private, spiritual reflection. But perhaps the only way to reimagine who we are and what we are each entitled to is to dig deep into our backyards and recognize that this land was never ours to begin with.